Take Notes: An Overview on Documentation

- director863

- Nov 5, 2025

- 4 min read

By: Ashton Becks, MT Intern

When I discovered the profession of music therapy, I was first intrigued by the way that music was a powerful conduit for helping all people. Once I began my secondary education, the thing that solidified my interest was the scientific, empirical nature of this modality. Music therapy has been built on evidence based practice and actual results seen and shared, and this begins with session documentation. So, I’ve taken some time to research what Eric Waldon (MT-BC) has to say about Clinical Documentation Article (Waldon 2016).pdf. Here’s what I’ve found.

First, documentation is defined in this article as “any form of information to describe care in a client’s record that assists with treatment and aids communication between professionals (Waldon 2016).” I typically think of documentation as written progress notes, but it also includes medical scans, audio, video, and test results. Since it is 2025, most records are kept digitally. Things like the electronic record system and format of documentation varies from private practices (like PMT), hospitals, and other spaces that music therapy is provided, but elements of documentations such as assessments, progress notes, treatment planning, discharge paperwork, and referrals, just to name a few, must be included regardless.

This leads me to my second observation: one of the primary functions of documentation is compliance (Waldon 2016). There is a standard of care in the field of music therapy, and a major part of this is maintaining records and following American Music Therapy Association (AMTA) Guidelines. There is a specific domain created by AMTA that describes the elements of what makes documentation compliant to clinical practice standards. Some examples include ensuring a signature of a MT-BC along with a date, description of intervention techniques, and regularity of documentation. Implementing these checks and expectations for practice ensure clients have trust in all therapists in the field. This level of excellence branches out into therapeutic relationships, musicianship, and other domain areas, but documentation is a tangible way to see written evidence of veracity.

My third observation is that an equally important function of documentation is communication. Communication between team members and other health care professionals is imperative to ensure quality treatment and care. Waldon mentions four key components of communication and gives a few scenarios of why this is important. Credibility comes from a qualified professional with specific skills and knowledge, accuracy comes from information that is relevant and true to clinical events, clarity comes from coherent writing in a concise way relating to clinical reality, and timeliness comes from order of events in order to further support accuracy. This becomes particularly important in many ways. When a therapist needs coverage, the therapist covering should be able to provide relevant and quality treatment based on the documentation provided. When a therapist moves states, a client’s new therapist will need to have as much clinical guidance as to how to continue quality treatment through documentation. When a client is receiving additional support from another health care professional (SLP, PT, etc.), documentation from a music therapist can support their findings in continuing to improve their services. These are a few examples, but you see the idea. Good communication shows the more information that can be provided by a trusted source, the more supported a client can be.

Waldon quotes Keith Boone (2011) in his article: “What was important yesterday may no longer be relevant now, but information that seemed irrelevant then might be important today.” I was talking to a friend the other day about how I see videos on social media that I think are hilarious at the moment, but when I try and find said video to show to someone else, I can never find it. A very Gen Z example of me, I know, but this funny example really is a phenomenon we all experience in various ways. This problem becomes far more serious when a therapist is caring for a client. It would be malpractice for a therapist to haphazardly attempt various interventions or guess what work to progress toward goals, and it would also harm the client’s treatment for a therapist to not continue to document events over time. This quote sums up my last observation that documentation simultaneously reinforces accountability and displays progress. Since documentation per the guidelines is to be credible, accurate, clear, and timely, this gives clear, empirical indicators about what has worked, what hasn’t worked, what adjustments have been made and their results, and general progress. Proper documentation can lead to discovering findings that you may not be able to remember over time. When referred back to, it is an unbiased means of encouragement of the work that has been done to care for a client well! Like the quote, though it may seem insignificant when writing, documentation will grant you a glimpse into progress when it resurfaces.

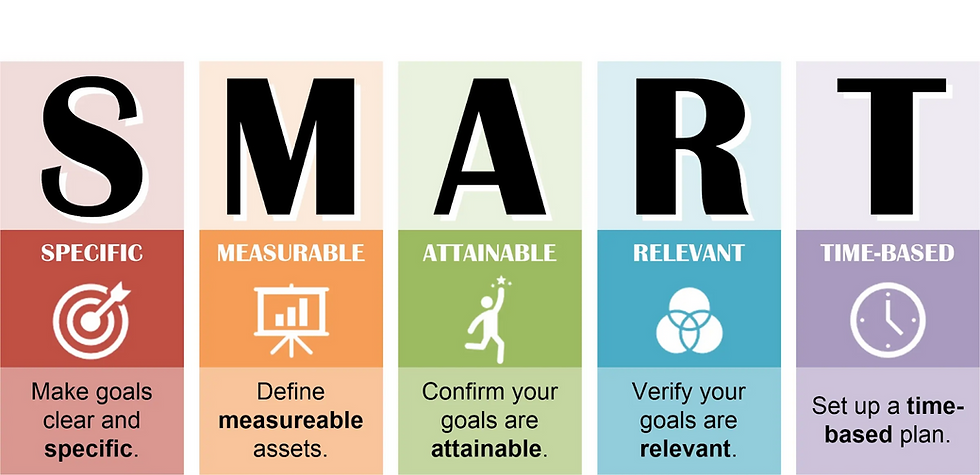

So, how about your life notes? What are some ways you can document your days in such a way that, though it may seem irrelevant now, will prove to the future “you” that progress has been made? SMART Goals (the photo provided) could be a start, or maybe a thankfulness journey. A “Grateful (Insta)Gram profile with pictures and captions of a fitness journey. Even just taking time to sit in the fall scenery could prove fruitful. Happy notetaking, everyone!

Comments